Most people have heard of hip and knee replacements and may even know someone that’s had one, but did you know that the shoulder is the third most common joint replaced?

Every year in the United States, 150,000 patients successfully undergo shoulder replacement surgery, which is up from around 40,000 per year since I started practicing over 15 years ago. So why has the popularity of shoulder replacement exploded over the last few decades?

The answer is undoubtedly the reverse shoulder replacement, or reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA), which in my opinion is the biggest advancement in shoulder surgery in the last few decades—and possibly the biggest advancement in all of orthopedics.

How the Shoulder Works

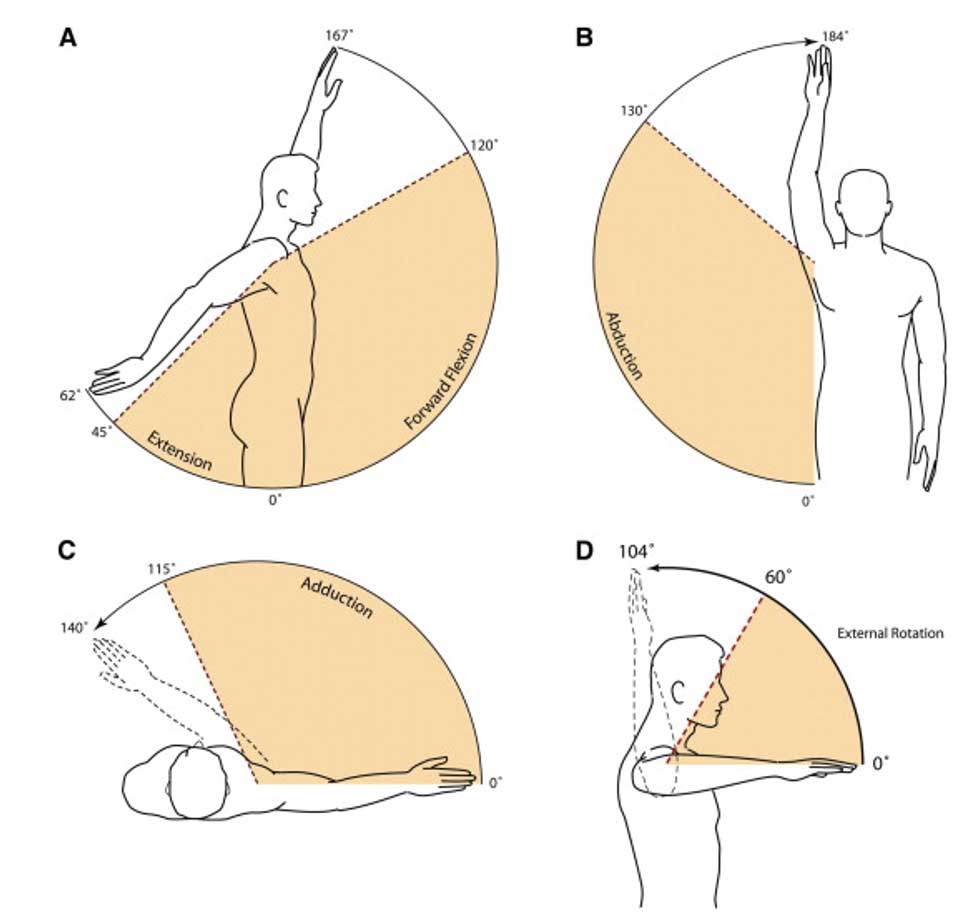

The human shoulder is a marvel of evolution. Almost nowhere in the mechanical world exists a joint that allows 160° of motion in every direction, requires no local maintenance, and can last for more than 70 years without wearing out (figure 1).

Even universal (U) and constant-velocity (CV) joints—some of the most dynamic joints in modern mechanical engineering—can’t provide the extremes of motion that nature has provided in the human shoulder. As ingenious as these engineering devices are, they still require frequent routine maintenance, external lubrication, and rebuilding of worn out parts (figure 2).

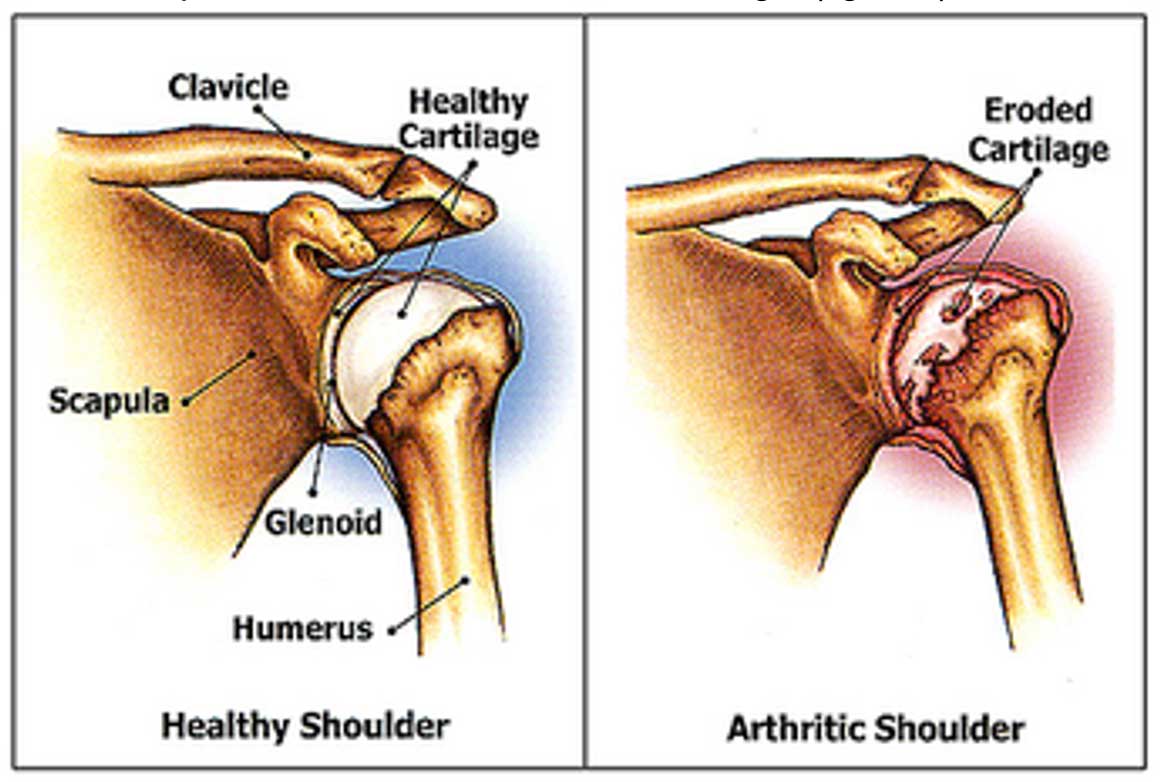

Joint cartilage which provides a smooth low friction surface for one bone to move relative to another, requires none of this, and lasts much longer (figure 3).

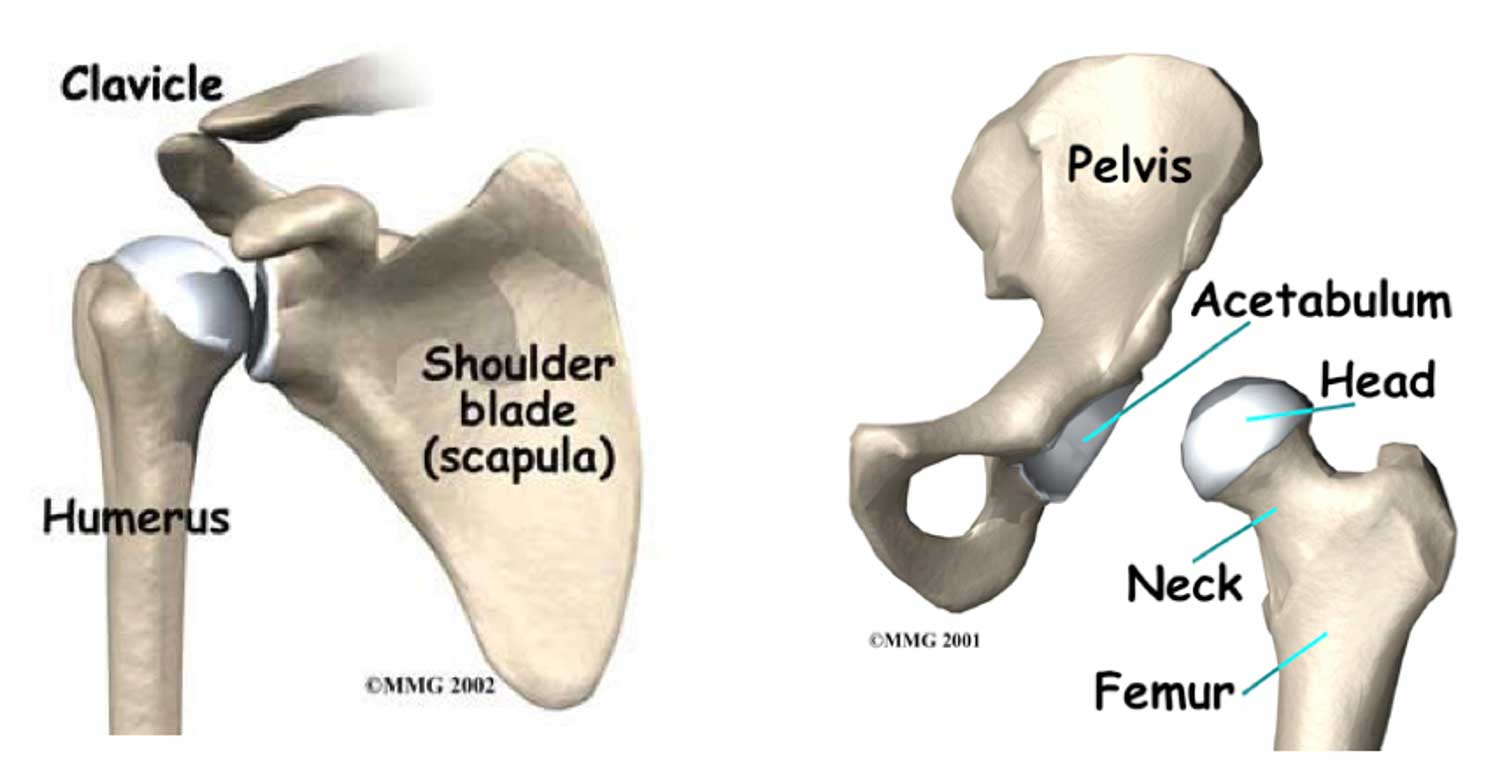

When we compare the shoulder to the other major ball and socket joint in the body, namely the hip, we see that the shoulder has a much greater range of motion. This is because the hip socket covers about half of the ball, while the shoulder socket only covers about 1/3 of the ball (figure 4).

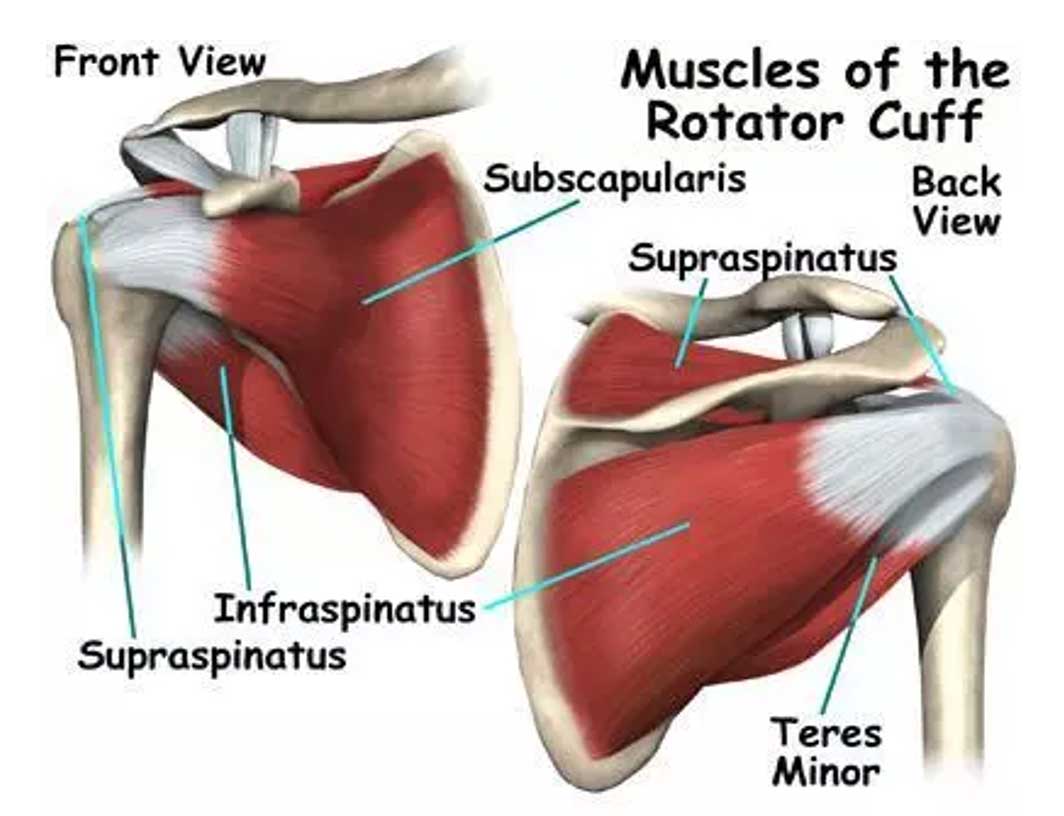

This lack of coverage allows for a much greater range of motion, but the tradeoff is that the shoulder is less stable. As a result, the shoulder relies much more on soft tissue constraints to allow the arm to move in space and keep the ball from popping out of the socket (AKA dislocating). These soft tissues include ligaments, the joint capsule, and muscles—most importantly, the rotator cuff (figure 5).

If these soft tissues are damaged, the ball may not stay centered in the socket, which can cause pain, weakness, difficulty moving the arm, or even dislocation. Most people have heard of dislocating a shoulder, but have you ever heard of anyone dislocating a hip? Probably not. The reason for this is that because the hip socket covers so much more of the ball, it’s very difficult to dislocate a hip; this is not so true of the shoulder.

Shoulder Replacement Surgery

Unfortunately, sometimes the shoulder cartilage wears out, which is when shoulder replacement surgery becomes an option. The type of shoulder replacement we do depends on what else is happening with the other parts of the shoulder, including the bones, the capsule, and especially the rotator cuff.

A standard (anatomic) shoulder replacement relies on the bones and soft tissues around the shoulder to be intact in order for it to function properly and prevent the ball from partially or completely sliding out of the socket. If these constraints are not intact, a standard shoulder replacement will not function correctly, can prematurely fail, and could even partially or completely dislocate.

However, by reversing the positions of the ball and socket, the modern reverse shoulder replacement is designed to make up for some of these deficiencies—namely, the rotator cuff—and to some degree bone loss from severe wear by relying more on the deltoid muscle to keep the ball centered in the socket and to move the arm in space.

As you can imagine, this means that although a reverse shoulder replacement can make up for loss of the rotator cuff, it requires a functioning deltoid. This works out nicely for those of us treating shoulder problems, since rotator cuff disease is the most common disease of the shoulder, while deltoid deficiency is actually pretty rare. As such, we can now treat a huge number of patients for which there really weren’t good treatment options before the reverse shoulder replacement was available.

The Reverse Shoulder Replacement

So what is a reverse shoulder replacement and why do we call it “reverse”? Simply put, the shoulder is a ball and socket type joint. The surfaces of the ball and socket are covered with cartilage, which creates a very low friction surface to allow them to move relative to each other (figure 3).

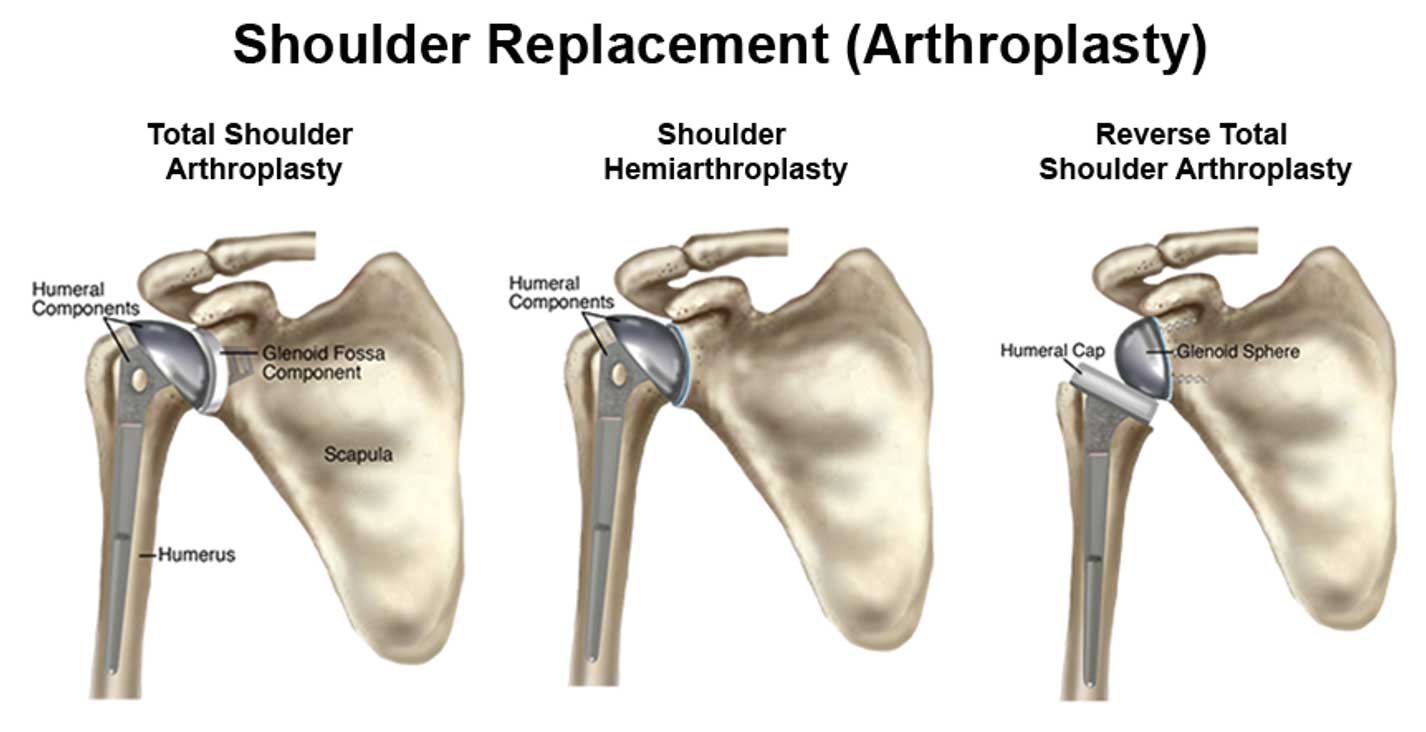

If the cartilage wears out, the shoulder can be replaced with a standard (anatomic) total shoulder replacement or total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA or ATSA), which replaces the native ball with a metal ball and resurfaces the socket with a plastic cap (figures 3, 6).

A total shoulder replacement replaces both sides of the joint—meaning the ball as well as the socket—whereas a partial shoulder replacement, or hemiarthroplasty, only replaces the ball if, for example, just the ball is damaged. Typically, the prosthetic ball is attached to a metal stem that goes down the arm bone (the humerus) which basically functions as a mount for the metal ball.

In a reverse shoulder replacement, the locations of the ball and socket components are switched, placing the ball where the socket normally would be and the socket where the ball used to be (figure 6).

Read the Next Post on Dr. Klug’s Shoulder Surgery Invention

If you think you need or are interested in learning more about shoulder surgery—including a reverse shoulder replacement—we’re happy to help. Please reach out to book an appointment with Dr. Klug.